Welcome to flaneuring, a newsletter featuring new resources on urban & beyond, insights, and photography.

an insight

When I first started learning about urban design, I naturally began with the popular books — Walkable City, Streetfight, Happy City, among others. These books are excellent, and they do a great job at giving you the big picture. But because they’re working at that scale, it’s naturally hard for them to fit in all the nuance.

Pretty quickly, I noticed they all circle back to the same two names: Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses. Jacobs is usually framed as the community-minded underdog; Moses as the top-down power broker. Those quick references build a neat, surface-level mental model: Jacobs good, Moses bad. Even if the underlying facts hold up, that kind of shorthand is still risky — it flattens real people into symbols, and I didn’t want that to keep settling into my brain with every new book I read.

Several years into this learning journey, I felt like I had gotten to know Jacobs fairly well, mostly through her own writing — from the well-known Death and Life of Great American Cities to the less-known but actually my favorite, Dark Age Ahead. Moses, on the other hand, remained more of a silhouette.

That’s why I picked up Robert Caro’s The Power Broker. This biography promises to break whatever two-dimensional mold I’d built around Moses (assuming there’s something to break).

What shaped him? What did his early years look like? How did he accumulate so much influence? How did he change over time?

I’m only on Chapter 5, but can already feel the picture shifting.

Here are a few highlights from the first chapters:

“When Robert Moses began building state parks and parkways during the 1920’s, twenty-nine states didn’t have a single state park; six had only one each. Roads uninterrupted by crossings at grade and set off by landscaping were almost nonexistent. Most proposals for parks outside cities were so limited in scope that, even if they had been adopted, they would have been inadequate. The handful of visionaries who dreamed of large parks were utterly unable to translate their dreams into reality. […] But in 1923, after tramping alone for months over sand spits and almost wild tracts of Long Island woodland, Robert Moses mapped out a system of state parks there that would cover forty thousand acres and would be linked together — and to New York City — by broad parkways. And by 1929, Moses had actually built the system he had dreamed of, hacking it out in a series of merciless vendettas against wealth and wealth’s power that became almost a legend — to the public and to public officials and engineers from all over the country who came to Long Island to marvel at his work.”

“In the evening of Robert Moses’ forty-four years of power, New York, so bright with promise forty-four years before, was a city in chaos and despair. His highways and bridges and tunnels were awesome — taken as a whole the most awesome urban improvement in the history of mankind — but no aspect of those highways and bridges and tunnels was as awesome as the congestion on them. He had built more housing than any public official in history, but the city was starved for housing, more starved, if possible, than when he had started building, and the people who lived in that housing hated it — hated it, James Baldwin could write, ‘almost as much as the policemen, and this is saying a great deal.’ He had built great monuments and great parks, but people were afraid to travel to or walk around them.”

[About his college years at Yale] “And if he was not included in the more select social circles of the class, he created a circle of his own, a small coterie of persons with like interests, a coterie within which he was the acknowledged leader.”

What I've learned about Moses so far is that although he was undeniably born into wealth and privilege, he also seemed to carry the mark of someone who didn't quite fit the elite social circles — especially in his college years, where his Jewish background (even if he didn't practice) and his intense intellectual focus set him apart. His mother, Bella, and his grandmother clearly pass down a love of building, directness, idealism, and Moses made that his own. He also had a deep desire for learning, which increasingly feels like a clue to how he transformed into the figure he became.

I'll share more reflections as I keep reading. And if you've read this book, I'd love to hear your thoughts too.

snapshot

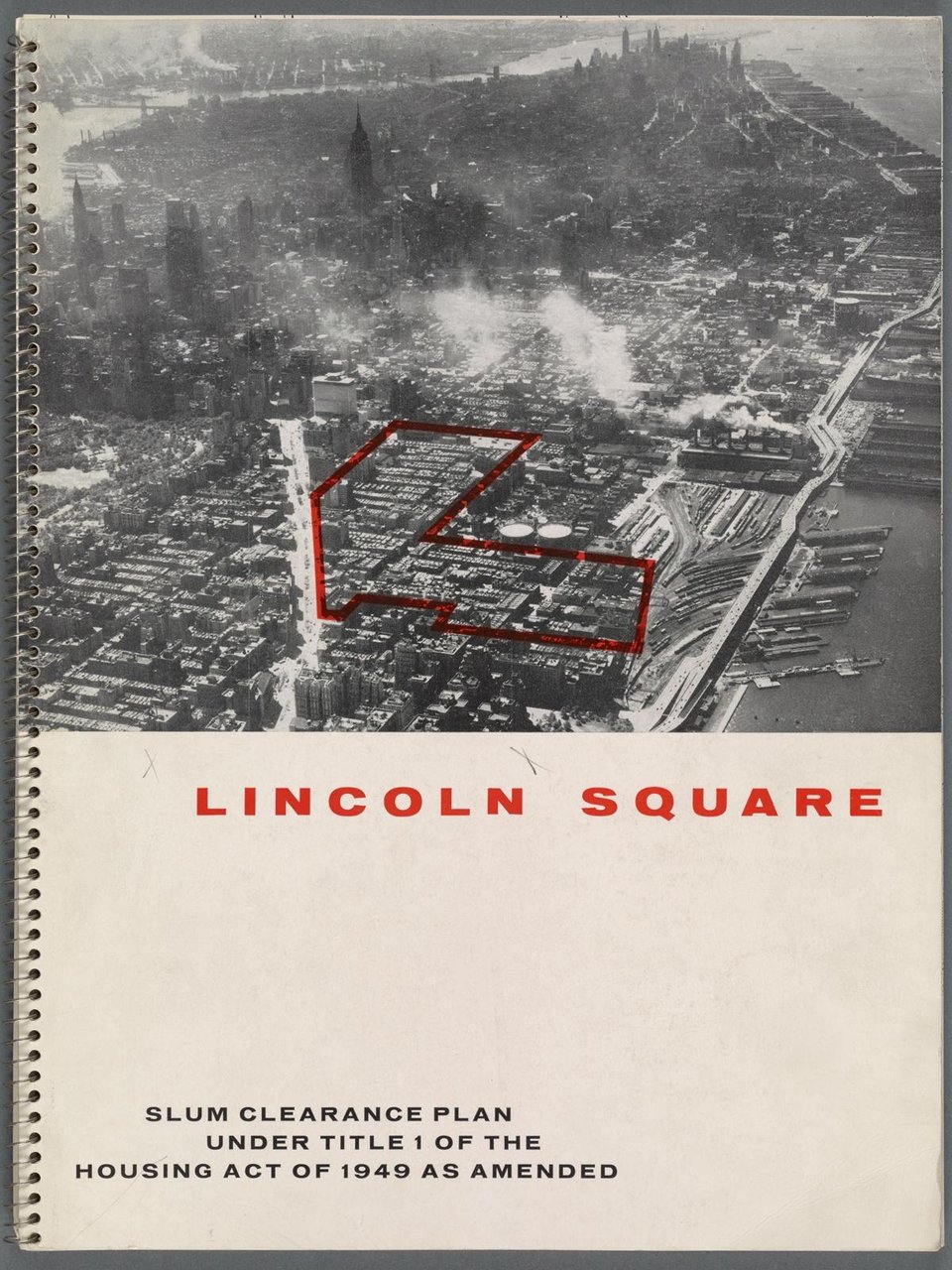

You've most likely heard of the iconic Lincoln Center in New York City, or even been there for a performance. Robert Moses left his mark there too — picking the site, consolidating the land, and moving the project through the city. Like many of his projects, Lincoln Center wasn’t built on empty land; it displaced the people who lived here before.

The original Lincoln Square clearance map makes that impact clear:

new resource

If you also love traveling to cities, and if a good coffee + a long walk is your ideal way to explore, you might enjoy what I put together. I added 14 mini city guides to the site: short lists of hotels, coffee shops, streets worth walking, and places worth visiting. Some are simple lists, others have a few extra tips. All link out to Google Maps. Hope they’re helpful for your next wander!